My Friend Carl Jensen - Adventures in Growing Willow

We got lost on the way there. Our much newer, fancier-than-we’ve-ever-had car has sat nav in the dash. On day two of ownership we hadn’t quite figured out how it worked and managed to programme in the wrong address. After a slight detour through Lanark, pit stop at a garden centre, up a single track road, over a hill and finally crossing back over the motorway we’d left half an hour previously, we found the layby that we’d been told to park in. We climbed out of the car, looking back and forth between the map I’d been sent and the landscape around us to find the waymarkers. Along a road, over a fence, down a bank, over a stream and around a stone dyke, we found what we were looking for - a small group of willow enthusiasts and Anna Liebmann’s willow coppice.

Anna sorting through freshly cut willow

I’d met Anna a few weeks previously at the Central Scotland School of Craft in Dunblane. I was given a place on a hen basket making course and shed a few tears of excitement enroute. After a tricky year where I’d been pretty tied to my house, farm and family, it felt unbelievably fortunate to be “out out” learning something I had wanted to for so long.

Under Anna’s gentle tutelage, we learned how to construct this traditional frame basket, used in the past to transport broody hens between farms and made popular in the 1960’s by Bridgette Bardot. We learned how to manipulate willow in different ways - creating ribs and weavers from different lengths of Somerset grown willow. I managed to construct a rather rough, but exceedingly useful basket of my own - mistakes riddled throughout that I can clearly see, but still held my lunch as we ventured out for the day.

an in-progress and a completed hen basket at the central scotland school of craft

Plants have always been my first love. Armed with a plant encyclopedia and a badly behaved terrier named Snickers, I spent my childhood exploring the woods, attempting to identify all of the wildflowers on our 40 acres. An eccentric thing even then, I firmly believed the oak trees that surrounded our pond were my friends and that the greatest crime ever committed was the time one of my brothers was sent to mow down the hill of multiflora roses (At age 10, I didn’t understand about invasive species).

I have changed so little in the 30 years since that I still come home with pockets full of my finds (a scrap of honeysuckle fibre, a handful of alder cones and a very nice stone all were emptied from my trousers before doing laundry this morning). It is really no surprise that my other love, making, has become intertwined with the plants I love so dearly.

After almost 15 years of working full time in the craft industry - I am no longer only interested in the making. In the early years, I just wanted to create the shawl/hat/jumper, but now I want to know the whole process - from the soil up. How are the things we make farmed? Where do they go at the end of their lifecycle? And how do we propagate both the skills and the materials for the making I love so much?

So when Anna asked for volunteers to help with her willow harvest, I jumped at the chance to dig deeper, literally, - volunteering Kevin and I to this corner of a field along a highway in deep Lanarkshire.

multicoloured willow bundles

As we neared the patch, the reds, oranges, purples and greens of the willow stood out starkly against the grey of February in Scotland. Spread out in sections over about an eighth of an acre, the site is a mix of larger pollards and coppice—both types of repeated cutting of trees to stimulate new growth. According to Wikipedia:

Coppicing is a traditional method of woodland management which exploits the capacity of many species of trees to put out new shoots from their stump or roots if cut down. In a coppiced wood, which is called a copse, young tree stems are repeatedly cut down to near ground level, resulting in a stool. New growth emerges, and after a number of years, the coppiced tree is harvested, and the cycle begins anew. Pollarding is a similar process carried out at a higher level on the tree in order to prevent grazing animals from eating new shoots

Overstood coppices dot the countryside. Traditionally valuable resources for charcoal making, firewood, basketmaking, bark for tanning and tree hay, coppiced hazel, alder, willow and oak stands can be found in many remaining woodlands. We have an old hazel coppice here at Gartur - long past its 7 year harvesting cycle - but would have been a valuable resource when the property was young most likely for firewood.

Willow is planted close together, about 12 inches apart, to encourage the new growth to stretch up in long straight lengths towards the sun. With names like Carl Jensen, Harrisons and Dickie Meadows, I couldn’t help but picture old men crowded together at the pub as we walked perpendicular to the multi-coloured rows. Harvested every year, the shoots grow out of the ground in knots called stools. You cut them close to the ground and then sort by lengths and remove any branched or damaged ones.

Anna uses her own willow for basket making, but still needs to buy in more for teaching and specific uses like ribs and buff willow — willow steamed to remove the bark. Harvesting the willow for the year is time consuming and potentially back breaking (my hamstrings are still stiff today!). Each basket uses a surprising amount of willow to make, so to grow enough willow to make baskets at scale is a lot of work.

In theory, a willow coppice is easy to create. Fresh cuttings about 10 inches long will readily root once stuck in the ground. Willow patches are normally mulched with plastic landscape fabric, wool or silage tarp to keep out competing weeds. Planted in winter, they are left for a year to grow before they are cut back to the ground to repeat the cycle. Willow is harvested annually in winter before the sap starts to rise. Other tree coppices have longer cycles - hazel is a 7 year cycle, oak can be up to 25 years.

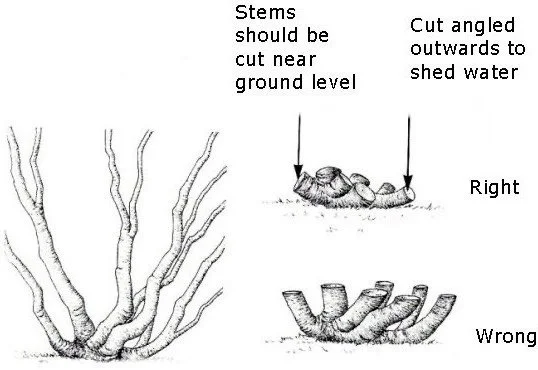

Which way to plant willow

Our own experience of willow growing has been unsurprisingly less successful than the easy breezy approach above. Two years ago, in a bout of deep winter enthusiasm I planted two patches of willow for my basket weaving dreams. Vaguely following advice on the internet, I rolled out a length of landscape fabric and stuck my cuttings through (making sure the willow shoots along the stem were pointing up) and walked away. In retrospect, I made three vital mistakes:

I didn’t keep them wet enough and they struggled to root.

The ones that did root, didn’t have much of a chance as I didn’t mulch far enough around the sticks and grass soon took over, strangling the tiny saplings

The death knell for any remaining willow was that I planted my stand far too close to where the goats could reach them and they leaned over the fence and nibbled the top of every single willow tree, killing any that made it that far.

Anna mentioned similar hooved snackers, in the form of deer roaming the area. She showed us willow lengths with branches shooting out where deer had foraged, creating willow less suitable for weaving.

Once the willow was cut and sorted, we bundled the lengths and Anna showed us how to make a rose tie with another length of willow for hauling up the hill. The off cuts were handed out as payment for the day - a dozen Carl Jensens came home with me to hopefully create our own new and improved patch. Carl Jensen (salix purpurea) was bred specifically to create the ideal basket willow when shortages hit the Netherlands basketmaking community. According to Anna, the beginnings of her crop was smuggled in a suitcase here to the UK by another willow grower.

Learning from Anna as well as my previous struggles, the cuttings went straight into a bucket along with a few others a friend sent. This year, I am rooting them first in water to give them a better chance of taking off. A new corner of the field has been chosen, complete with electric fencing and an abundance of more mulching to give them the best chance possible.

So here’s hoping this time next winter I will have my own willow patch of dreams…

You can find Anna here:

Another great follow for weaving inspiration is the fab Foraged Fibre on Instagram

https://www.instagram.com/foragedfibres/

Green Aspirations, our neighbours, are hosting another coppicing weekend on the 14th-16th of April.

https://www.greenaspirationsscotland.co.uk/event-details/the-great-scottish-coppice-gathering